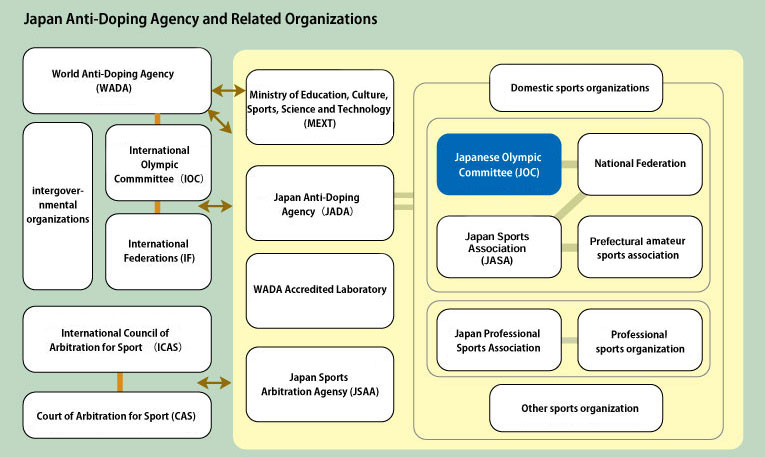

The JOC is taking an active approach to anti-doping movements, in line with those proposed by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Action is being taken alongside JADA, the Japan Anti-Doping Agency, an organization formed to promote anti-doping strategies within Japan.

Specific activities include conducting doping tests on athletes attending international multi-sport events such as the Olympic Games. These allow for dissemination of accurate information concerning anti-doping measures.

The term "doping" refers to the use of any substance or method which illegally enhances one's athletic performance. Doping is an act which violates the basic principle of sport: fair play.

Every sport must be a fair competition in which the rightful winner receives the credit it deserves, and allowing doping defeats the very purpose of sport. Doping is also harmful to an athlete's health, and can have adverse social consequences.

For these reasons, a serious approach to anti-doping strategies (prohibiting and eradicating doping) is greatly needed within the sporting arena.

The first case of doping in sport is thought to have been an incident that occurred in 1865 at a canal swimming event in Amsterdam. In 1886, the first known death caused by stimulant use was recorded at a cycling event, and in 1960 a similar incident took place at an Olympic Games. The drug (stimulant) related death of a cyclist at the 1960 Rome Olympics prompted an official doping testing system to be established at the 1968 Olympic Games in Grenoble (winter) and Mexico (summer).

In the beginning, athletes were tested for narcotics and stimulants, with anabolic steroids joining the list at the 1979 Montreal Games. At the Seoul Games in 1988, 100m sprinter Ben Johnson was stripped of his gold medal after testing positive for the anabolic steroid stanozolol, a drug which had previously been difficult to detect. At the 1998 Tour de France, several cases of erythropoietin use were discovered, and from the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games blood tests were conducted on athletes to screen for erythropoietin. Since the introduction of doping tests, many athletes have tested positive for illicit substance use. A case that is perhaps fresh in everyone's memory is that of Adrian Annus, a hammer thrower who, at the 2004 Athens Olympics, had his gold medal confiscated for forging urine test results and refusing to undergo testing.

From the 1960s, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was responsible for the majority of anti-doping activities. However, since it is desirable for anti-doping to be carried out by an independent, impartial organization, and because doping is an issue not just for the sporting world but for society as a whole, the IOC joined with various national governments to establish WADA, the World Anti-Doping Agency. As a member of WADA's executive committee, Japan has established the Asia/Oceania regional office of WADA at the Japan Institute of Sport Sciences, located in Tokyo's Nishigaoka. The office is actively involved in the anti-doping movement.

In March 2003, WADA's anti-doping rules were adopted as the global standard to apply to all sports, and the basic principles for anti-doping activities were established. According to WADA regulations, there are eight categories classifying doping. In addition to positive doping tests results, verbal evidence incriminating an athlete, refusing to undergo doping testing, obstructing doping testing, or acts performed by staff to assist with doping are considered equivalent to doping as well.

The Japan Anti-Doping Agency (JADA), Japan's domestic anti-doping agency, was established in 2001 within the buildings of the Japan Institute of Sports Science located in Tokyo's Nishigaoka. The agency is responsible for all anti-doping activities in Japan, including determining standard doping test processes for Japan, authorizing doping control officers (DCOs), implementing doping control procedures, and anti-doping education.